Round and Round

750 words, 4 minute read. With Claude Sonnet and Midjourney.

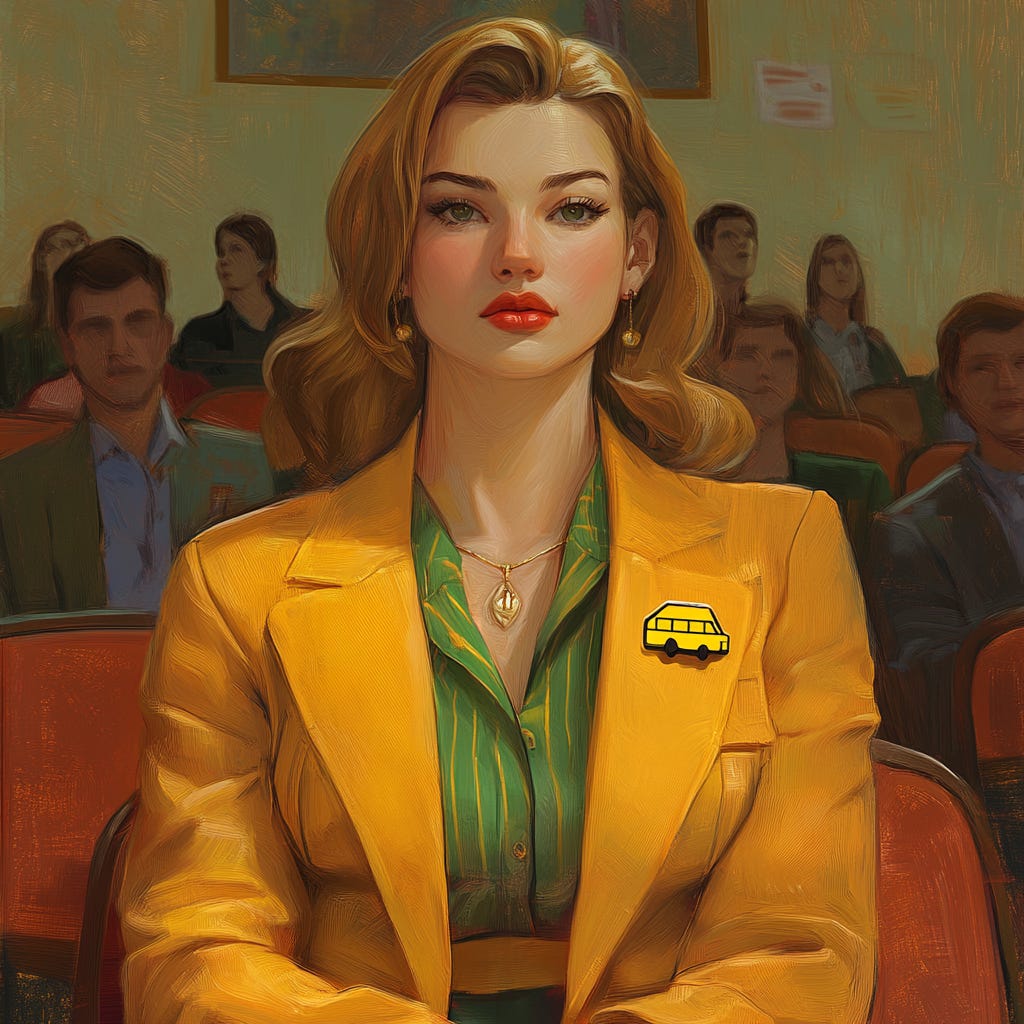

Superintendent Santiago fastened her grandmother's pin—a miniature yellow school bus from Charlotte, 1975—to her collar before slipping the small leather journal into her jacket pocket. Her assistant Marcus appeared at the door.

"Capacity crowd, Dr. Santiago. And Dr. Wilson from the Foundation is here personally."

Santiago nodded. "I'll speak with her briefly before we begin."

---

The amphitheater hummed with tension as Santiago took her place at the podium. Behind her, the poster showed the "Excellence Through Neutrality" seal of the National Educational Neutrality Act of 2028. In the side section sat Dr. Eleanor Wilson, her weathered lapel bearing the same yellow bus pin.

"Thank you all for coming tonight," Santiago began. "The implementation of NENA has created significant changes, and I'm here to listen to your concerns."

A woman stood immediately, her face a glower. "My daughter spent three years qualifying for the advanced algebra track. Last week, her cohort was disbanded for not meeting 'demographic balance requirements.' She's devastated." Her voice tightened. "In 1975, they told my mother her school was being shut down for 'the greater good.' Now I'm hearing the same justification used to limit my daughter's potential."

Before Santiago could respond, a father near the front rose. "My son was reassigned to a 'balanced neuro-cognitive environment' yesterday. He has processing advantages but emotional regulation challenges. His previous pod accommodated both." The man's knuckles whitened. "Now he's struggling. When we talk about balance, whose needs matter?"

Santiago stepped from behind the podium. "These situations highlight exactly what makes this transition so difficult. We have children with unique combinations of abilities and challenges."

From the back, a man with in a red jacket stood. "Then why force one model on everyone? My twins were in different pods because they have different abilities. Now they're together because their profiles balance the room's diversity algorithm." His voice carried clearly. "You're *bussing* us backward, Superintendent."

"Mr. Alvarez," Santiago acknowledged, "you've chosen an interesting word—'bussing.'" She gestured to where Dr. Wilson sat. "Dr. Eleanor Wilson is with us tonight. Besides founding the Neural Accessibility Foundation, she was herself a student during the integration efforts of the 1970s."

Wilson stood, commanding attention despite her small stature. "I was fourteen when they closed my neighborhood school. Every morning at 5:30, I boarded a yellow bus to cross town. My parents protested. Said I was being used as a social experiment."

A young mother rose. "With respect, Dr. Wilson, that was about racial segregation. This is about cognitive ability grouping. It's completely different."

"Different variables, same equation," Wilson replied calmly. "Every generation believes their sorting mechanisms are more objective than the last. We thought IQ tests were scientific. Now those measures seem primitive." She gestured to the parents around the room. "How will your cognitive diversity algorithms look to your grandchildren?"

Santiago pulled her grandmother's journal from her pocket. "My mother wrote about feeling out of place in 1975, about the unfairness of being forced to change. But she also wrote this, ten years later: 'Today I watched them dismantle the bussing program. They called it a return to neighborhood schools. But I see the invisible lines being redrawn. The resources shifting back. The opportunities clustering. We call it natural, but there's nothing natural about opportunity hoarding.'"

Santiago closed the journal. "I implement these changes because the law requires it. But the heart of what we're struggling with hasn't changed in fifty years: Can excellence and equity coexist? Must one child's acceleration come at the cost of another's opportunity?"

From the middle section, a mother stood. "My son has processing delays. Before, he was isolated in a remedial pod. Last week, an advanced student helped him with a coding problem—showed him an approach that worked with his thinking style. Maybe they both learned something valuable."

Santiago straightened her shoulders. "The law requires statistical balance, but it doesn't dictate our implementation approach. I'm establishing a parent-educator task force to design flexible pod structures—allowing for both specialized instruction and meaningful integration, where students might move between configurations based on subject area and learning needs."

"And how exactly would that work under NENA?" Alvarez challenged.

"The same way the most successful integration efforts worked in the 1970s," Santiago replied. "Not by pretending differences don't exist, but by ensuring resources and quality instruction follow all children, wherever they learn."