Frontiersman

Expansion. 2,000 words, 10 minute read. With Claude Sonnet and Midjourney.

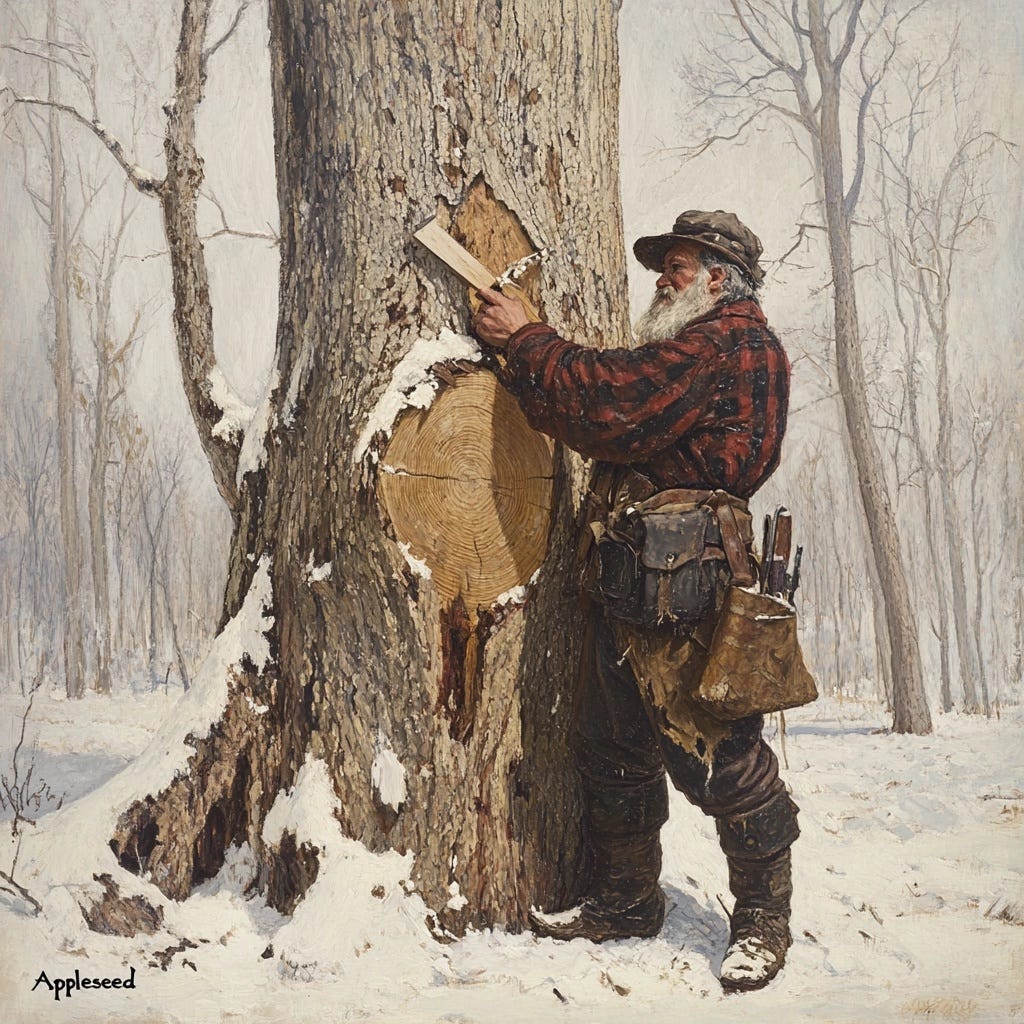

The oak split beneath Johnny's axe, revealing pale heartwood that had never seen daylight. He paused, tracing the tree rings with calloused fingers. Fifty-seven rings—older than the United States itself. The tree had witnessed the Menominee hunts, French traders, British soldiers, and now him: American, inexorable, certain.

February 1837. Wisconsin Territory, three years from statehood. Johnny MacIntosh—known as "Appleseed" to those who'd traveled west with him from Pennsylvania—wiped sweat despite the bitter cold. His land grant, signed by President Jackson himself, crackled in his pocket like a promise.

Twenty paces away lay a circle of stones—a Menominee fire ring, abandoned just months earlier after the forced removal. The tribe had managed these forests for generations, burning underbrush selectively, harvesting with ceremonies and limitations. Now the land belonged to those with different visions.

Johnny's journal entry that night was brief: Cleared two acres today. Good soil beneath. The shadows here are older than my understanding.

"The demolition permits finally cleared," Mikhail said, sliding the tablet across Dimitry's desk in the Mariupol Business Center. "Block 17 is scheduled for next Tuesday."

April 2027. Eastern Ukraine—or what international maps now labeled the Azov Autonomous Region following the ceasefire. Fifteen months since the final artillery shells had fallen. Three months since Dimitry Vladimirovich Sokolov had arrived from Moscow to oversee what official documents called "reconstruction" and "economic revitalization."

Through the floor-to-ceiling windows, excavators devoured the remnants of pre-war apartment blocks. The machines seemed almost animal in their methodical destruction, jaws closing on concrete and rebar, crushing memories into manageable fragments.

"The old woman still refuses relocation?" Dimitry asked, though he already knew the answer.

Mikhail shifted uncomfortably. "Katerina Orlova. Her family's documents date to 1791. Cossack settlers."

"History is full of ironies," Dimitry murmured. "Have you shown her the architectural renderings? Perhaps seeing the future would ease her transition."

That night, his journal entry, like Johnny's two centuries earlier, was equally terse: Block 17 clearance proceeding. The resistance here is older than they understand.

By April, Wisconsin's ground had softened enough for planting. Johnny pressed apple seeds into dark earth with reverence bordering on ritual. Each sapling represented both food and claim—roots that would anchor his descendants to this soil. The Homestead Act wouldn't exist for another twenty-five years, but the principle was already embedded in American consciousness: improve the land, and it becomes yours.

He'd chosen this clearing carefully—formerly a Menominee summer camp, the ground already fertilized by generations of fish remains and forest management. Why start from scratch when others had already done the work?

Henderson arrived as Johnny planted the twentieth sapling, bearing letters from the settlement and news from the East.

"Congress is debating another removal bill," Henderson said, squatting beside the fresh-turned earth. "Pushing the tribes beyond the Mississippi. Permanent separation, they're calling it."

"Makes sense," Johnny replied, not looking up from his work. "Can't have a proper nation with divided loyalties."

Henderson chewed his lip, uncharacteristically thoughtful. "Spoke with a French trader yesterday who's married to a Menominee woman. Says their methods for growing corn yielded more than our techniques ever have. Said they had systems for everything—fishing, hunting, forestry—all worked out over centuries."

Johnny's hands stilled momentarily. "If they were so advanced, why aren't they still here?"

"Numbers. Guns. Smallpox." Henderson shrugged. "Not the same as being right."

That night, a figure materialized at the edge of Johnny's clearing—an old Menominee man, one of the few who had evaded removal. Neither spoke, but their eyes met across thirty yards of contested earth. The moment stretched until Johnny reached for his rifle. When he looked back, the man was gone.

In his dreams, Johnny walked through an orchard where each apple contained a tiny human heart.

"We've increased the relocation offer by twenty percent," Dimitry told the Moscow investors over video conference. "The remaining holdouts will accept eventually. Economic reality is persuasive."

Beyond his window, the skeleton of New Mariupol rose like a promise—glass and steel replacing the Soviet-era concrete that had defined the city for generations. Historical preservation committees had carefully selected which pre-war landmarks would remain as "cultural touchpoints." Everything else would be modern, efficient, Russian.

After the call, Dimitry visited the demolition site personally. Block 17 stood like an island amid a sea of construction—a three-story building with faded blue plaster, somehow intact despite the artillery barrage that had leveled its neighbors.

Katerina Orlova waited on the steps as if expecting him. Eighty-four years old, spine straight as a banner pole. Her eyes mapped his face with unsettling precision.

"Mrs. Orlova," he began in Russian, "I've come to show you—"

"Your drawings of the future," she finished, her Ukrainian accent coloring each word. "I've seen similar drawings before. In 1932, when Stalin's men came. In 1941, when Hitler's architects arrived. In 1991, when Ukrainian developers promised capitalism would save us." She gestured toward the ruined city. "Each time, someone burns what was built before and calls it progress."

Something cold settled in Dimitry's stomach. "This isn't the same."

"It never is, until it is." She handed him a tarnished key. "My grandfather's. The lock it opened disappeared when the Soviets collectivized our farm. He kept it anyway. Some things persist beyond their usefulness, Mr. Sokolov."

That night, Dimitry dreamed of endless construction sites where each brick contained a tiny, beating heart.

By summer's end, Johnny's cabin had taken form—notched logs chinked with clay, a stone chimney drawing smoke into the vast Wisconsin sky. The apple saplings stood knee-high, their leaves fluttering in the breeze like green flags claiming territory.

The territorial governor visited in August, accompanied by land speculators from Chicago and a military escort. They spoke of railroads, factories, cities rising from wilderness—a manifest destiny unfolding according to divine plan.

"You're the vanguard, MacIntosh," the governor declared, surveying the cleared fields. "Men like you transform savage lands into civilization."

That evening, as twilight painted the sky, Johnny found himself wandering to the forest edge. A half-mile in, he discovered a clearing he'd never noticed before. At its center stood a massive oak, its branches creating a perfect circle of shadow. Beneath it lay hundreds of small carved figures—animals, people, symbols he didn't recognize.

A voice behind him spoke softly in accented English: "Our history books."

Johnny whirled to find the old Menominee man watching him, neither hostile nor welcoming. Just observing.

"These carvings," the old man continued, "tell how to live here. Which plants heal. When to burn the underbrush. How to ensure the deer return each season. Seven generations of knowledge."

Johnny's hand hovered near his knife. "Books are better. Permanent."

"Nothing is permanent." The old man gestured toward the carvings. "But some things endure if enough people remember them."

Later, Johnny stood at his property edge, watching darkness claim the forest. For a moment—brief but disorienting—he felt like a temporary intrusion rather than the rightful beginning of something permanent. Then he turned back toward his cabin's warm windows, the sensation fading with each step homeward.

Dimitry's children arrived for their New Year's visit, marveling at Mariupol's transformation. His son, fascinated by the construction equipment, asked endless questions about demolition techniques and architectural plans. His daughter, sixteen and increasingly political, watched everything with quiet intensity.

"The museum director in Moscow said this region has changed hands seventeen times in recorded history," she noted as they toured the harbor development. "Scythians, Greeks, Mongols, Ottomans, Russians, Soviets, Ukrainians, and now..."

"And now we're rebuilding what war destroyed," Dimitry finished for her. "Creating opportunities in a place abandoned by history."

That evening, they attended the opening gala for the financial district—investors, military officials, and politicians celebrating the future rising from ruins. Champagne flowed as drones performed an aerial light show above the harbor, forming the Russian double-headed eagle before morphing into abstract patterns of progress and prosperity.

Stepping onto the terrace for air, Dimitry found his daughter staring toward Block 17—still standing, illuminated by construction floodlights, Katerina Orlova's windows glowing defiantly.

"My history teacher says occupation always follows the same pattern," his daughter said without turning. "First comes military force, then economic investment, then cultural replacement. He says it's the same whether it's nineteenth-century America or twenty-first century anywhere."

Dimitry's jaw tightened. "Your teacher should stick to established curriculum."

"He says history is the established curriculum. That's why powerful men always try to rewrite it." She finally turned to face him. "Is that what you're doing here, Papa? Rewriting?"

Before he could answer, his phone buzzed—the Moscow minister requesting his presence inside. The conversation remained unfinished, hanging between them like a bridge half-built.

Autumn 1842. Johnny's apple trees bore fruit for the first time—small, tart apples that would improve with each generation of careful grafting and selection. His children harvested them in baskets woven using techniques Johnny had learned, ironically, from a Menominee woman who now sold crafts to settlers at the growing trading post.

The Wisconsin Territory had transformed in five years. Settlements had become towns; trading posts had become markets. A stagecoach now ran weekly from Chicago. Survey teams plotted railroad routes through forests that had never known the sound of steam whistles.

Henderson, visiting less frequently as his own farm expanded, brought news and whiskey one crisp October evening.

"They found that old Indian," he said, warming his hands by Johnny's fire. "The one who used to watch from the trees. Frozen to death last winter, sitting against an oak with all those carvings you told me about."

Something tightened in Johnny's chest. "What happened to the carvings?"

"Loggers took the whole clearing last month. Railroad needs ties." Henderson studied Johnny's face. "You look like you've seen a ghost."

"Just thinking about time," Johnny replied. "Everything we build, someone else will inherit or destroy."

Later that night, unable to sleep, Johnny walked his orchard beneath the harvest moon. The apples hung like small lanterns among dark branches. His deed said this land was his, but standing among trees that would outlive him, the concept seemed suddenly absurd. How could anyone truly own something that had existed before them and would continue after?

For a disconcerting moment, he imagined the land beneath him as a palimpsest—layers of ownership and belonging repeatedly written, erased, and overwritten. His claim was just the newest ink, already fading even as he pressed it deeper.

Then his practical mind reasserted itself. He had work tomorrow—fences to mend, winter to prepare for, a future to secure. Whatever philosophical doubts plagued him in darkness would burn away in daylight's certainty.

February 2028. The demolition order for Block 17 received final approval after fifteen months of legal challenges. Dimitry watched from his office as the equipment assembled before dawn—a ballet of machinery choreographed for maximum efficiency.

Katerina Orlova had finally accepted relocation the previous week, after her doctor confirmed advanced heart disease. The old woman had extracted one concession: her family's icons would be installed in the new Orthodox church being built nearby. Cultural continuity within replacement—a concept Dimitry found both pragmatic and vaguely troubling.

As the excavator's arm rose against the pale winter sky, Dimitry's daughter called.

"I'm watching the livestream," she said without preamble. "The Ukrainian diaspora groups are sharing it everywhere."

Dimitry frowned. "It's just urban renewal."

"That's not what the comments say." He could hear her typing. "They're sharing before-and-after satellite images. Mapping demographic changes. Documenting cultural replacement methodologies."

"Those are politically motivated exaggerations."

"Maybe." Her voice softened. "Or maybe they're just doing what humans always do—remembering what others want forgotten."

The conversation lingered in Dimitry's mind as he watched the excavator's jaws close around the first section of Block 17. The building collapsed with surprising grace, decades of human lives reduced to rubble in moments.

For a brief, unsettling instant, Dimitry saw the construction site as future archaeologists might—layers of civilization compressed into strata, each generation building atop the ruins of the last, each believing their version would be permanent.

Then his phone buzzed with updates and congratulations from Moscow, pulling him back into the immediate, the practical, the certain. Whatever philosophical doubts troubled him would be buried beneath the foundations of progress—just as they had been for centuries before him, and would be for centuries after.

In that moment, separated by two hundred years but united by the same fundamental human pattern, Johnny MacIntosh and Dimitry Sokolov shared an identical thought, though neither would ever fully articulate it: The land endures; we are temporary. But while we're here, we'll pretend otherwise.