and yet the train barrels on

technological boycotts

The bailiff’s keys jangled against his belt as he crossed to the window. Maya Chen heard him twist the latch closed, muffling the chants from the street below: Clanker Collaborators. Clanker Collaborators. The rhythm had been steady since seven that morning.

She aligned her pen with the edge of her legal pad. Perpendicular. Exact. Her mentor had taught her that during pre-trial prep: control what you can control. The paper, the pen, the crease in her blazer. Not the tremor in her hands when she’d printed the final draft of the complaint three weeks ago, when she’d typed Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association v. Titan Press and felt like she was carving something permanent into the world.

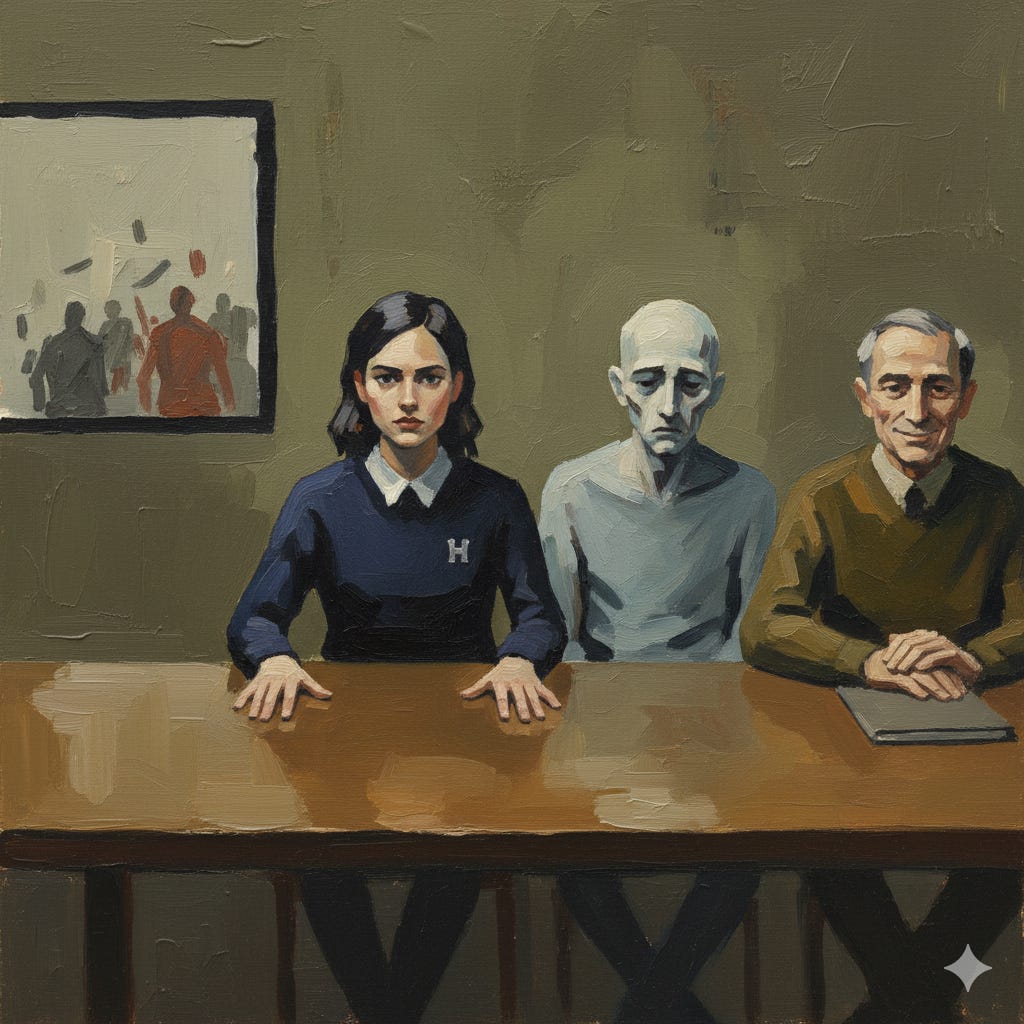

Across the aisle, David Reeves traced his pinky around the grain of the defense table. Maya had watched him do it four times since sitting down. He wore a sport coat with elbow patches—the kind of thing someone wears when they want you to know they’re a writer. Catherine Morgenstern sat beside him in a charcoal suit that probably cost more than Maya’s car, scrolling through her tablet with the bored efficiency of someone who’d won before walking in.

Judge Holbrook entered without ceremony. Everyone stood. The judge was smaller than she looked in her official photo, and when she sat, she did so with less gravitas than Maya had expected. In one hand was a paper hotel coffee cup, cheap cardboard already showing signs of leaks.

“Counsel.” Holbrook opened the file. “Ms. Chen, this is your motion for preliminary injunction. I’ve reviewed your brief. I’ve reviewed the opposition. I have questions.”

Maya’s prepared opening dissolved. “Yes, Your Honor.”

“Mr. Reeves published a book. You want me to stop Titan Press from selling it.” Holbrook looked up. “Walk me through your standing.”

Maya had rehearsed this exact question—she’d stood in her apartment at two in the morning, arguing to her bathroom mirror. “SFWA represents eleven thousand professional authors. When Titan Press published The Copper Moon knowing Mr. Reeves used AI generation, they legitimized a practice that directly harms our members’ economic interests. Every copy sold—”

“How?” Holbrook’s coffee sat untouched. “How does Mr. Reeves’s book harm your members? Did he plagiarize their work?”

“No, Your Honor, but—”

“Did he violate a contract with SFWA?”

“SFWA wasn’t party to—”

“Did he commit fraud against your organization?”

Maya felt the questions like darts flying overhead. “Your Honor, the harm is systemic. When publishers accept AI-assisted manuscripts, they create an incentive structure that devalues human authorship. Our members compete for limited shelf space, limited marketing budgets, limited advances. Mr. Reeves admitted on his personal blog that he ‘used AI to draft difficult scenes’ in his book. That’s not speculation. Those are his words.”

Holbrook wrote something. Maya couldn’t see what.

“Ms. Morgenstern, response?”

Catherine stood without hurry. “Your Honor, my client used software. He used it the way writers have used dictionaries, thesauruses, and grammar checkers. He remains the author. He conceived the plot, developed the characters, revised extensively. Plaintiff wants this court to parse exactly how much computational assistance renders someone’s speech no longer their own. That’s not a legal question. That’s philosophy, and it’s not justiciable.”

“He said AI.” Maya didn’t mean to speak, but the words came out anyway. “Not ‘grammar checker.’ Not ‘dictionary.’ He was specific.”

Catherine turned. Her expression didn’t change, but something in her posture sharpened. “Ms. Chen would like to depose my client about his creative process. She’d like to put electrodes on his skull and measure which neurons fired when he wrote which sentence. The First Amendment forecloses that inquiry.”

“Your Honor—” Maya started.

“Let her finish,” Holbrook said.

Catherine continued as if Maya hadn’t spoken. “Plaintiff submitted an expert report analyzing Mr. Reeves’s prose for ‘AI markers.’ Syntactic patterns, they claim. Metaphor frequency distributions. Your Honor, this expert ran Mr. Reeves’s work through probabilistic analysis software powered by AI and claimed the output proved machine generation. Do you see the problem? They’re using AI to detect AI, then asking this court to ban books based on the result.”

Maya flipped through her notes, looking for the rebuttal she’d prepared. Her hands left damp prints on the pages. “Our expert is a computational linguist from MIT. His methodology—”

“His methodology is irrelevant,” Catherine said, “because the underlying question is unconstitutional. Plaintiff wants to regulate speech based on the tools used to create it. The First Amendment doesn’t contain an approved-implements list.”

Holbrook held up one finger. Catherine sat. The courtroom settled into silence except for someone’s phone buzzing in the gallery—two short pulses, then nothing.

“Ms. Chen,” the judge said. “I want to understand your limiting principle. If I grant this injunction, what happens next? What about authors who dictate their books to transcription software? What about ghostwriters? Translators? Editors who substantially revise manuscripts?”

“Those involve human judgment at every step.” Maya heard how defensive she sounded. She tried to modulate, to find the tone her mentor used—calm, authoritative. “An editor doesn’t generate text. They refine human-created work.”

“And Mr. Reeves claims he refined AI-generated suggestions,” Holbrook said. “How do I distinguish those scenarios?”

Maya looked down at her notes. The words blurred. She’d written human creativity and underlined it three times, but now the phrase looked childish, inadequate. “The distinction is... Your Honor, there’s a qualitative difference between tools that assist human creation and tools that replace it.”

“Who decides where that line is?” Holbrook’s voice wasn’t unkind, but it was relentless. “You? SFWA? This court? Under what constitutional framework?”

The silence stretched. Maya became aware of her breathing, too loud in her own ears. Behind her, someone in the gallery shifted, and the bench creaked.

“Ms. Chen, I’m going to give you something you might not want.” Holbrook closed the file. “I’m going to be direct. This lawsuit asks me to determine whether Mr. Reeves’s book is authentic speech or something less protected. It asks me to evaluate his creative process and judge whether it meets some standard of acceptable authorship. That inquiry violates the First Amendment. Not because AI is intrinsically good or bad, not because I’m making a policy judgment about technology, but because the government—and this court is the government—cannot condition speech protection on approval of the speaker’s methods. We don’t do that. We can’t do that. Not under our Constitution.”

Maya opened her mouth. Nothing came out.

“Motion denied.” Holbrook picked up her pen. “The injunction is denied, and I’m dismissing the complaint with prejudice. Plaintiff lacks standing, and even if standing existed, the relief sought is unconstitutional. Ms. Morgenstern, submit your order. We’re adjourned.”

The gavel fell once.

Maya stayed in her seat as the courtroom emptied. Catherine gathered her materials and left without looking back. David Reeves paused at the door, glanced toward Maya, then followed his attorney out.

The bailiff approached. “Ma’am? We’re closing up.”

“Right.” Maya stacked her papers. She’d been so sure. The law was supposed to protect people, and writers were people, and when you put those facts together the answer seemed obvious.

She walked out into the hallway where SFWA members were already on their phones, voices rising in anger and disbelief. Outside, through the courthouse windows, the protestors were still chanting. The same rhythm. The same words. Clanker Collaborators.

Inside, in a courtroom that smelled like old coffee and furniture polish, a judge had spoken, and the world hadn’t changed at all except in the one way that mattered: the line Maya thought she’d been defending had turned out to be somewhere else entirely, or nowhere, or drawn in a language the law refused to read.